There were 32 waterways named Mill Creek within the area that is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park when it was formed in the 1930s.

Needless to say, that led to some confusion.

``The park service had to change the names because of rescue operations,'' said Park Ranger Mike Meldrum Friday within spitting distance of Cable Mill in Cades Cove.

There were as many as seven grist mills within Cades Cove alone when the Park was formed, Meldrum said.

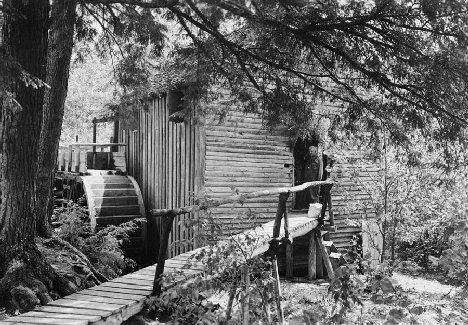

One of the most successful -- and enduring -- grist mills in the cove was the Cable Mill, built in 1867 by its namesake, John Cable. The mill, which processed logs, wheat and corn and was originally operated by millwright Daniel Ledbetter, continued to function in some fashion until the 1920s, and was actually still -- informally -- in use when the Park was formed.

Renovations about the middle of the last century and the replacement of the mill wheel four years ago has ensured the mill continues to operate much as it did almost 150 years ago.

Thus the arrival Friday of about 200 mill enthusiasts and preservationists from across the country. The visitors to Cable Mill were over from Pigeon Forge, on a field trip in concert with the Society for the Preservation of Old Mills (SPOOM) 2004 conference, which runs through Sunday.

``It's kind of an honor,'' Meldrum said. ``Their mission is the same as the Park mission,'' he said: the preservation of historic structures and cultural history.

The conference is held each year in different areas around the Eastern United States. East Tennessee, with its plethora of old -- albeit dwindling -- mills was the perfect fit, said SPOOM board member John Lovett.

``We try to pick areas where we can visit as many mills in a tight area as we have time,'' said Lovett, who with his wife, Jane, operates Falls Mill & Country Store in Belvidere.

The Cable Mill was the first of three the conference attendees will be visiting during their Pigeon Forge stay. The group will also visit an old Pigeon Forge mill and a restored mill relocated to the Museum of Appalachian History in Norris.

``We try to help educate, to preserve old mills and related Americana that is disappearing,'' Lovett said.

And mills are closely -- if not irrevocably -- linked to the history of the country, noted SPOOM board President Kevin Johnson.

``It's important to show future generations how their grandfathers and predecessors lived,'' said Johnson, who hails from Beloit, Wis.

``In the Midwest, every town started with a mill. It was a source of food and building supplies, people came, and a town developed around it.

``The miller was an important figure in the community.''

In the case of the John Cable Mill -- Meldrum referred to Cable as an entrepreneur -- it served as a valuable social outlet as well as a commodity source.

Cove residents would gather once a week, usually Saturday, and have their grain or corn processed into meal and flour for a fee of 8 percent of whatever was ground.

There was once a structure in the area known as ``a warming shed'' where people would wait their turn with the miller.

``This was not just a place to get your corn ground; other than church, this was the social outlet,'' Meldrum said. ``They'd talk about the same things we do today -- each other, crops, who was sick, who was getting married.

``The social aspect of the mill was as important as the grinding aspect.

``Both played a part in the culture,'' of Cades Cove and the rest of the Appalachians, Meldrum said, and as members of SPOOM will attest, many points beyond.

The group has ``several thousand'' mills in its database, Johnson said.

``Every year we hear about mills not even in our database.''