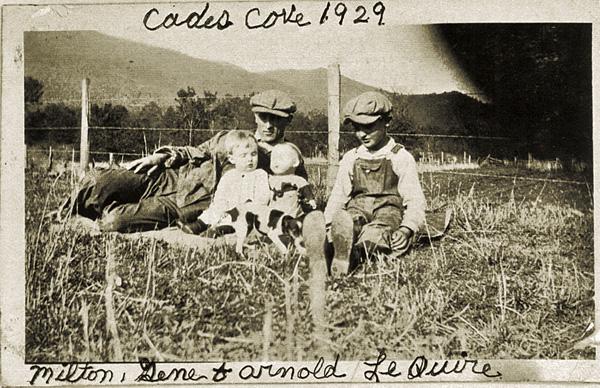

LeQuire Family of Cades Cove

Living in Cades Cove unique experience

"Families were more than just neighbors in mountain community"

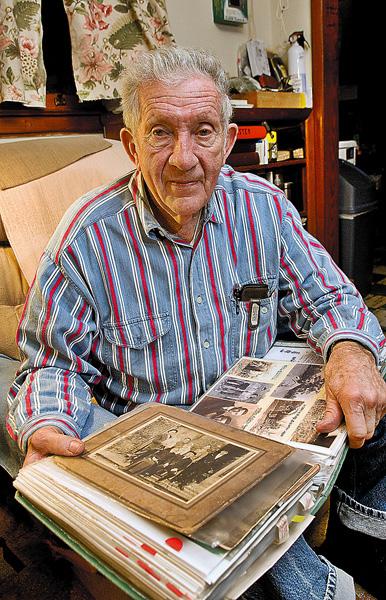

Gene LeQuire shows off a scrapbook of Cades Cove photographs at his home in Blount County. LeQuire, 80, was an infant when the U.S. government forced his family from their 100-acre Cades Cove farm in Nov. 1929.

Maybe a handful of people can still tell you what it was like to live in Cades Cove.

The rest of us just have to imagine it.

But if we listen to the old-timers, we find that the pre-park Cades Cove was a community where everybody was everybody's neighbor, where different families were woven together like a fabric through marriage and childbirth, where life was certainly not easy but folks still had pretty much all they needed.

Friends and neighbors

White settlers first moved into the cove in the early 1800s, according to the National Park Service. At its peak, the population reached about 625 in the 1850s. It fell to just a few hundred soon after.

By the 1930s, authorities were buying up acreage for Great Smoky Mountains National Park, ensuring an end to human habitation. The last of the original cove residents was Kermit Caughron, who lived for decades in a former one-room schoolhouse about three-fourths of the way around the 11-mile Cades Cove loop road. He stayed there until shortly before his death in 1999 at age 86.

Whether it was the geography, the slow communications and travel or simply a desire to be left alone, people in this idyllic valley surrounded by mountain peaks were mostly insulated from the outside.

Cove native Gene LeQuire, a self-designated "packrat," treasures pictures and letters from his family and the stories he was told of those days. His family owned 100 acres across from John Oliver's cabin.

"People took care of each other in the cove," he said.

Born Aug. 5, 1928, LeQuire, like so many others there, was delivered by a midwife named Polly Harmon.

Willard Abbott also came into the world in the hands of a midwife, on Sept. 6, 1925.

Both men tell of existences where families grew almost everything they ate year-round, buying only the staples and things they could not produce themselves, like coffee, sugar, clothes and shoes.

The work was hard, but these were resourceful people without a smidgen of laziness.

LeQuire relates the story of how his father's family all came down with the flu in the pandemic of 1918. The snow was knee-deep and the cattle were in the barn. Directly, an old man and three boys showed up.

They would not venture inside for fear of catching the disease, but they told the sick family they would feed and milk the cows. They placed the milk on the porch along with some firewood and left.

Abbott's wife, Jean, said her husband was born during a terrible drought, when most of the springs in the valley went dry. During Abbott's mother's convalescence, a neighbor woman from across the valley walked over, bringing water from her spring, which was still running.

County Mayor Jerry Cunningham retells the story his mother, Norma Shields Cunningham, told of how her father, the man the mayor knew as "Papa," would put her as a child on a horse with seven or eight bags of corn and send her to the mill to get it ground.

She would wave as she passed each successive farm, and the people would watch her until she was out of sight to make sure she stayed safe.

"Maybe it was the 11th Commandment," Cunningham said, "to help your neighbor."

If a barn burned, he said, everybody joined in building it back. When his dad was sick and could not get the corn crop in, the neighbors did it for him.

Both LeQuire and Abbott told how cove residents all knew the tones of the various bells at the four churches in the valley. And if one of the bells rang in the middle of a workday, all labor ceased until the bell stopped ringing.

The bells would signify that someone had died, and the ringing would be followed by a slow tolling, one clang for each year of the dead person's life.

Everyone knew who had been sick and probably could tell the dead person's identity by counting the tolls. Workers, sometimes 10 to 20, would lay down their tools and immediately head for the church to dig the grave.

Farewell to the homeplace

In such a close-knit culture, it is no surprise that the cove people did not give up their homes easily.

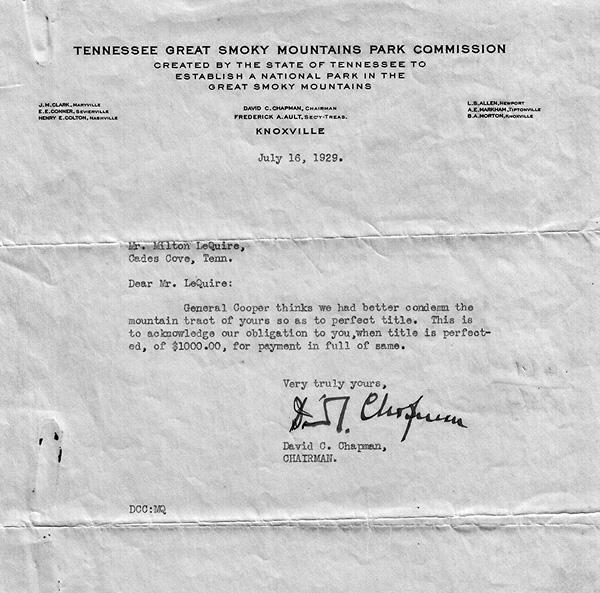

Some, like Gene LeQuire's father, Milton, recognized the forces that were working to build the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the late 1920s were probably too formidable to fight. He took his money and bought a farm and a car on Pleasant Hill Road in Blount County.

Gene LeQuire, who was about 18 months old at the time, lives on the farm today.

Abbott was 8 years old when his father, Elmer E. Abbott, took his settlement money, rented a truck and motored out to a newly bought farm on Clendenen Road in Maryville. He says Gene LeQuire is his distant kin.

Elmer Abbott also bought a car and placed the balance of the proceeds in a bank - which promptly failed.

Some who did not immediately reinvest their settlement in land lost it all when the bank they had entrusted with their money placed a closed sign on the door.

Abbott remembers some in the cove who vowed never to be moved off the land and backed up their promise with a shotgun.

That's why, Abbott said, men sent by the government to appraise cove land for purchase were often accompanied by security guards.

Jean Abbott said her mother-in-law, Rhoda Abbott, got the largest settlement of anyone in the cove - $18,000 - but then "grieved herself to death. She never got over it."

It is the sacrifice that these people made - were forced to make - that allows 21st-century visitors to see the cove as it is, a more or less pastoral oasis in a maddeningly frenetic world.

And here's a somewhat ugly thought to ponder: What would Cades Cove be like today if it were not in a national park?

Published Dec 21-2008 Knoxville News Sentinel

by Staff Robert Wilson Placed here with permission.

Surnames are in Bold Click here to read Gene's story

Site © Gloria Motter, All Rights Reserved for CCPA

From the webmaster: My husband & I was Blessed to have met Gene and Jo, also Lendell at Old Timers Day in the Cove many years ago singing under the big ole oak tree. We always enjoyed his talks about history in the Cove. Miss his singing and playing down there on that big rock.

Gene and Jo Lequire are charter members of the CCPA; Gene also serves on the Board of Directors. They have presented programs and music for several special CCPA events.

LeQuires celebrate 60th wedding anniversary today

Originally published: The Daily Times, July 22. 2009

Gene and Ruby Jo (Williams) LeQuire, of Maryville, are celebrating their 60th wedding anniversary today.

The couple were married July 22, 1949, at Pleasant Hill Methodist Church. The Rev. Gleaves Farmer officiated.

Their family includes children Judy Marie Waters and Connie Elaine Bright, both of Maryville. They have seven grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren.

Mr. LeQuire is retired from Cherokee Lumber Company and Waters Equipment. Mrs. LeQuire is retired from Blount Memorial Hospital.

They are members of Tuckaleechee Baptist Church and the Cades Cove Preservation Association.

LeQuire one room home